Remember utopia?

When it comes to tech and politics, utopia and dystopia are closer than they appear

Welcome back to the This Day In Esoteric Political History newsletter. Each week, a member of our team (or a friend of the show) gathers together bits of America’s past and attempts to find a throughline that might add a little understanding to our current moment.

Here’s what happened over the week ahead in American history…

July 11

1796: The United States takes possession of Fort Detroit from Great Britain under the terms of the Jay Treaty

1864: Confederate forces attempt to invade Washington, D.C. during the Battle of Fort Stevens

1944: President Franklin Roosevelt announces that he will run for a fourth term

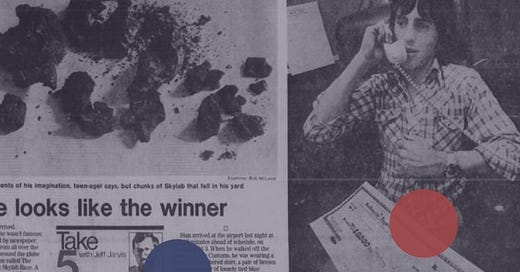

1979: Americans and others around the world are watching the skies as the first space station, Skylab, comes hurtling back down to earth

July 12

1804: Former United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton dies after a pistol duel with Vice President Aaron Burr

1957: US Surgeon General Leroy Burney (himself a smoker) connects cigarette use with lung cancer

July 13

1861: A treaty is signed between the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes and the Confederate States of America

1960: John F. Kennedy wins the Democratic nomination for President

1964: A woman's name, Senator Margaret Chase Smith, is entered for nomination at a major party convention (RNC) for the first time

July 14

1918: Quentin Roosevelt, the son of President Theodore Roosevelt, is shot down and killed by a German plane in France

1944 : A formerly enslaved man by the name of Nelson Hackett is being sent back to the United States after having escaped to Canada. It would be the first — and last — time that the Canadian government would collaborate with the U.S. to return an escapee

July 15

1955: 18 Nobel laureates sign the Mainau Declaration against the use of nuclear weapons. It was initiated and drafted by German scientists Otto Hahn and Max Born

1964: Barry Goldwater is nominated as the Republican candidate for President

2006: Twitter launches, marking a significant development in social media

July 16

1790: Congress declares the city of Washington in the District of Columbia as the permanent capital of the United States

1863: Draft riots enter their fourth day in New York City

1945: The first test detonation of an atomic bomb occurs at Trinity Site, Alamogordo, New Mexico, as part of the Manhattan Project.

1969: Apollo 11 is launched, carrying the first men to land on the Moon.

July 17

1821: Spain cedes Florida to the United States, in Plaza Ferdinand VII in Pensacola

1975: Apollo 18 and Soyuz 19 dock in space, symbolizing international cooperation in space exploration.

1997: Robert Weaver, a housing expert and the first African American cabinet member, dies at 89.

In which we take the above collection of events and find themes, throughlines, rabbit holes and more. This week is Nicole Hemmer’s turn at the typewriter.

On July 16, 1945, the scientists working on the Manhattan Project in Alamogordo, New Mexico, detonated the first atomic bomb, ushering in the Atomic Age.

On the same day 24 years later, NASA launched the Apollo 11, which carried the astronauts who, just four days later, would become the first humans to step foot on the moon.

These two moments were intimately linked for Americans in the mid-20th century, products of unparalleled scientific innovation, fueled by extraordinary confidence, that rewrote humans’ relationship to the planet. One made it possible to end all life on Earth. The other made it possible to, for the first time, allow humans to touch other parts of the solar system.

The twinned utopias and dystopias of the era redefined life not only for Americans but for people across the globe. The use of nuclear weapons in war and the nuclear-arms race that followed led 18 Nobel laureates to sign the Mainau Declaration on July 15, 1955; within a year, another 34 Nobel laureates joined them. But the arms race continued.

The space race promised to be the antidote to this catastrophic, world-ending competition, offering a vision of cooperation that would lift humans above nation-state competitions toward a sense of global solidarity. On July 17, 1975, when Apollo 18 and Soyuz 19 docked in space, in the midst of a period of detente in the Cold War, it seemed as though that promise might be fulfilled. Two hours later, the two mission commanders exchanged the first international handshake in space.

The Atomic Age and the Space Age were not, however, opposing visions of the future but rather examples of how world-changing, military- and government-backed innovation had revolutionary power: the power to destroy as well as the power to create.

We often forget now that many Americans met the early days of the Atomic Age with joy and wonder, imagining how the world might be remade with nuclear science’s immense power and potentially limitless energy. A writer at The Nation magazine imagined the new weapons could be used “to dig canals, to break open mountain chains, to melt ice barriers, and generally to tidy up the awkward parts of the world.”

That mix of utopian and dystopian visions tied to new technologies can help us make sense of one other On This Day from this week: the launch of Twitter (R.I.P.) on July 15, 2006. The early days of social media came at a moment of soaring techno-utopianism, when social media like Twitter seemed poised to radically expand democratic participation, level hierarchies, and usher in a golden age of transparency, community, and creativity.

In the early 2010s, that techno-utopianism collapsed, giving way to fears that social media threatened the future of liberal democracy: enabling genocidal violence, destroying journalism, spreading disinformation, and sharpening partisan grievances.

The reason we see this push-pull of utopianism and dystopianism, optimism and pessimism, has less to do with unique features of these new technologies and more to do with the social and political systems in which these technologies are born. Visions of better futures speak to our hope and imagination; fears of annihilation speak to our capacity for violence and greed and self-destruction. It’s very much worth learning about new technologies and their capacities, but it’s just as important to make sense of the power structures from which they emerge, because in the end, the history of technology is also political history.

—Niki

If you like This Day, why not consider supporting the show? Our show, and the entire Radiotopia network, wouldn’t be possible without fans like you who invest in independent programs like ours. ❤️

Apple | Spotify | PocketCasts | YouTube | Twitter/X | Threads | Instagram